Author Archives: Chris Wohlwend

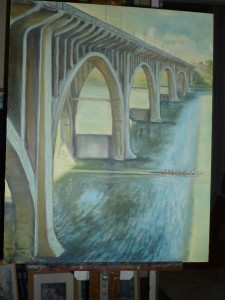

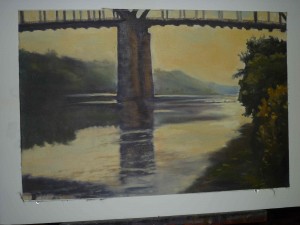

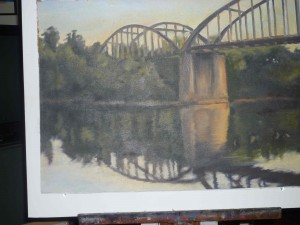

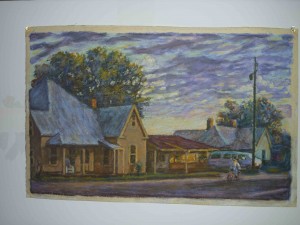

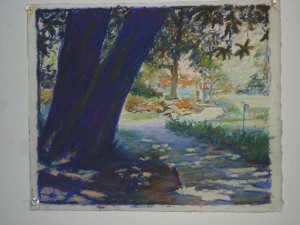

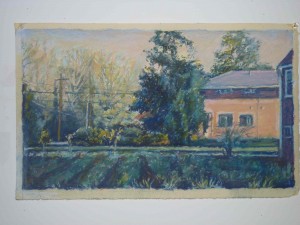

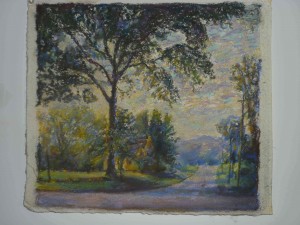

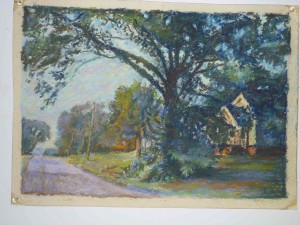

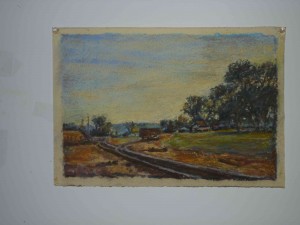

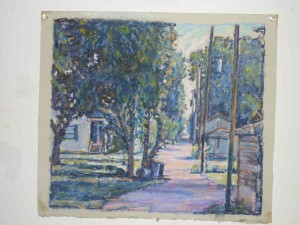

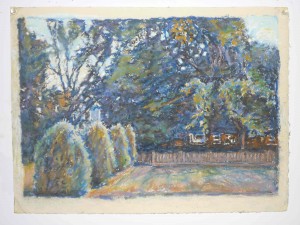

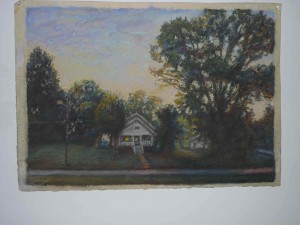

Rand Bradford, pastels

Reunion photos from Missy Albright

50th-Year Reunion

Forty-one members of the East High School class of 1963, ranked by many impartial observers as the top Mountaineer group in history, got together with assorted spouses and hangers-on at Calhoun’s on the River on July 13 for a grand remembrance of high school. Drink flowed, food was eaten, stories were told and stories were denied.

The ‘63ers came from locations near and far. Many had to overcome arduous physical obstacles.

Judy Trivett traveled from Australia. Pat Lamb and Charlie Jenkins from Texas. Sherry Wright and Jay Nelson and Becky Latham from South Carolina, Linda Cullop from south Georgia, Donna Poston from south Knoxville. Dauwn Snow came from Seymour, Nancy Snoderly from Pennsylvania, Nancy Reagan from Florida, Pat Maynard from Mississippi.

Vincent Kanipe and David Evans and Donna Dixon traveled from Halls, braving the heights of Black Oak Ridge. Several others also crossed mountains: Vonnie Easterday from Maryland, Jimmy Britton from Virginia, Lynda Bolt from North Carolina, Missy Albright from Gallatin, Loretta Harris from Kentucky. Earl Myers was allowed out of Alabama, Charlie Patterson furloughed from Rutledge.

Deanie Jenkins came from Maryville, Moyah Price from Powell, Larry Leibowitz from west Knoxville, Danny Meador from Gray, Clint Brewer from Murfreesboro, Rand Bradford from Fountain City. Knoxville was well-represented: Richard Hillard, Jerry Mikels, Jack Sherrod, Pat Lynch, Martha Sanders, Brenda Wright, Phyllis McDaniel, Kaye Williams, Betty Jo Doane, and Brenda Wheeler.

Joyce Maskell made it in spite of an accident a few weeks earlier, and Becky Mankel brought a comprehensive display of photos, Blue & Gray newspapers, and other memorabilia. Mary Lou Smith and Carolyn Miller, from the class of 1962, showed up to see that we behaved.

Sherry Wright’s superb rendition of Mr. Mountaineer was displayed beside the welcome desk. It was later signed by everyone in attendance. Photos were taken in front of Vincent Kanipe’s ‘56 Ford and David Evans’s ‘31 Model A.

After Charlie Patterson offered blessings of the food in observances of several religions (some known only to him), those in attendance feasted on turkey, pork loin, creamed spinach, and various gravies. Apple pie and chocolate mousse followed – miraculously no fights broke out over the last chocolate mousse.

Master of Ceremonies Chris Wohlwend then read Patsy Nelson’s note explaining why she could not attend. Then a note sent by Mary Jefferson, daughter of Dawn Jefferson, was read. Dawn passed away in 2011, and her daughter told how her mother had always talked fondly of her years at East, and of her love of her classmates. Other class members who are no longer with us were listed. Classmates whose whereabouts are unknown were also named. (Both lists are below).

Entertainment director Clint Brewer, looking dapper in a black bowler, then took over, and the tale-telling began. A story sent in by Pat Fraker, who was unable to attend, set the tone. She remembered an early-morning exchange between the irrepressible Mr. Fugate and the buttoned-up Miss Million, in which a dirty word – “sex” – was uttered. Live chickens in Miss Million’s classroom were then recalled.

David Evans, who described himself as a school-days “outlaw,” regaled everyone with the escapades that led to his frequent appearances before Mr. Bible. Joyce Maskell and Vincent Kanipe tried to explain their possession of flags from Holston Hills Country Club golf holes, obtained during late-night visits. Chris Wohlwend remembered a trip from Shoney’s on Broadway back to east Knoxville via Buffat Mill Road in which Joyce Maskall, Nancy Reagan, and Pat Maynard opted to get out of Richard Slack’s car rather than continue on with such gauche escorts.

Larry Leibowitz told how his homeroom Bible-reading experiences (he was always called on to read the verses at Christmas and Easter) led to his decision to become a lawyer.

Clint Brewer then told how Pat Lynch’s essay written for Mr. Fugate’s class was delivered as a love note, and Missy Albright explained the inner workings of the secret Yard Rollers Anonymous organization, with key participant Danny Meador providing more detail. The major roles of Patsy Nelson and Ralph Neal, who weren’t present to defend themselves, were noted.

Becky Mankel explained how she and Betty Jo Doane worked out a plan to avoid Miss Dowell’s English class, only to have the plan backfire, at least for Betty Jo. Diana Turley, always the serious scholar, figured into Betty Jo’s story of how she, Becky Mankel, Vonnie Easterday and Deanie Jenkins were aced out on a test by Diana, who misled the others into believing that she, too, had not studied for it.

Earl Myers noted that he was the youngest married student at East, having tied the knot with Janice when he was a junior. Others suggested that had he not been married, he would have gotten into even more trouble.

A dozen or so managed to make breakfast Sunday, where attempts were made to clarify stories from Saturday night. It was agreed that we would plan another reunion within the next couple of years, and that for those who live in the area, we will set up a monthly lunch or dinner. Details will follow, by email for those who have it, and by snail mail for those who do not.

Please post any address changes or information about any missing classmates in the comments section. Thanks to everyone for participating.

A memoir in haiku

Memorable moments

from a life spent studying the

world’s absurdity.

Who peed in your pants

Grandma asked when I was five.

Roy Rogers, I said.

A young smart-aleck,

the penchant for drollery

a gift from my dad.

Trying to play sax

at age12, eyes on the prof’s

red-haired teen daughter.

Park Junior lessons:

cherry bombs blasting commodes,

zip guns made in shop.

Seventh-grade classmate

taken by cops one day, an

unwilling dropout.

Housing a green snake

inside my locker — till he

left home, trailing screams.

School protection con

was a huge success — then Slack

cold-cocked the top boss.

In school parking lot

eighth grader’s Merc got rubber

– and our attention.

Turn of tap puts end

to a shower-room card game;

losers doubly soaked.

Six of us carried

Russell’s Crosley, setting it

outside the gym door.

Loud math-class squawking –

a live chicken wants out of

Miss Million’s desk.

A seven-week stint

washing dishes at Boy Scout camp,

honing cursing skills.

Foes became fast friends

after fight that started with taunt

of “sling fist, monkey”.

Teacher is snoring

in civics class so we learn

about anarchy.

Cool on Friday night:

back row at the Palace, eye

out for some action.

Cheerleaders, twirlers:

female form given wide-eyed,

attentive study.

Twisting at the hop –

moves so easy we each feel

we’re too cool for school.

Back-row BB drops;

study-hall teacher chasing

multitude of pings.

Before school day starts

piano boogie-woogie

shakes us and wakes us.

Driver’s ed images:

honking horns, dirty looks and

steering-wheel death grip.

Senior chapel blues:

student rockers’ gig ends when

teacher unplugs amp.

The real ‘West Wing”

The following essay was written for a magazine-writing class in 2009.

My political science teacher in college once broke down the definition of “politics” as “poly” meaning “many” and “ticks” meaning “parasites”. As he told our class this interpretation of politics’ definition, I agreed with him. At that point in my life, I viewed politics as several politicians meeting on Capitol Hill contemplating vital issues facing our nation and arguing over the necessary steps that needed to be taken in order to enhance the lives of American citizens.

While these outside views are widely shared by many Americans, they are no more than stereotypical beliefs. However, in the afternoon of Oct. 28, 2007, I found out first hand that I would be spending the spring 2008 semester as one of three interns in the White House Communications Office during President George W. Bush’s second term – an experience that would forever impact my views on United States politics.

One of my elder Chi Omega sorority sisters at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville did the White House speechwriting internship during the fall 2007 semester, and she was the one who inspired me to apply for the program. When I came to the University of Tennessee, I wanted to take a semester off to study abroad or engage in an internship program, and it was then I decided that perhaps D.C. could fulfill this role in my college experience.

I have not always had my eye on the political world. Originally from Loudon, a small, rural east Tennessee community with an estimated population of 4,000, I wanted to pursue a career in journalism so I could live the “Carrie Bradshaw dream” — move to New York following my college graduation, write about fashion, wear chic designer clothes and accessories as shown on HBO’s “Sex and the City” and enjoy brunch at a side-street cafe on a Saturday with friends discussing our current or non-existent romantic relationships. However, at the beginning of my sophomore year, as I began to “plan” out my life I began to realize that this New York fashion fantasy would not allow me to fulfill my goal of eventually settling down and raising a family; the long hours and extended traveling would always be an obstacle.

When I was in junior high school, NBC’s “The West Wing” was at its peak of television popularity. My mother was an avid viewer of the show after enjoying the film “The American President”, which influenced many features of “The West Wing”. I watched it with her occasionally on Wednesday evenings over our usual bag of Orville Redenbacher natural popcorn. I remember my favorite scenes of “The West Wing” were those that took place in the White House Press Briefing Room. Allison Janney’s character C.J., the press secretary, would always approach the podium with poise and dignity, taking crazed reporters’ questions, and I admired how, regardless of the question asked, she would deliver a response that was unbiased and pertinent. The White House’s Press Briefing Room in this show made the room appear to be a big, open conference room.

But as I attended my first White House Press Briefing, I was stunned and rather disappointed to discover that “The West Wing” really exaggerated the size of the room. The Press Briefing Room was about the size of a dining room in a fast food restaurant. I would estimate that eight to 10 rows of chairs lined the room with each major newspaper and broadcasting network having an assigned seat, with Helen Thomas, the Hearst newspaper columnist, sitting front and center because of her 57 years as a reporter covering the White House.

In New Line Cinema’s dark comedy,“Wag the Dog”, Robert De Niro portrays a Washington spin doctor who, only days before a presidential election, distracts the American people from a sex scandal by recruiting a Hollywood film producer, played by Dustin Hoffman, to fabricate a war with Albania.

The film opens with a question: “Why does a dog wag its tail? Because a dog is smarter than its tail. If the tail were smarter, the tail would wag the dog.” So the film wonders whether the dog wags the tail, or does the tail wag the dog? We see the tail moving, and we assume the dog is wagging it, but perhaps the tail is wagging the dog, and the dog is enjoying the attention. It refers to making a situation seem something it is not by creating the situation in such a way that the spectators react in a predetermined manner. With its tagline reading, “A comedy about truth, justice and other special effects,” “Wag the Dog” presents a possible scenario of what happens behind closed doors at the White House, and the tactics used to cover up a political figure’s flaws.

As a White House intern, I did not have a complete “all access pass” to know every detail and action going behind closed doors in the East and West Wings. Thanks to a particular former White House intern who wore a blue dress, we interns were required to wear a bright, red intern-labeled badge which limited our access to certain areas of the White House without a proper escort.But I was provided President Bush’s daily schedule and his views on political issues.

If I did not stand out enough in the political world of D.C., my first day going into work provided more evidence for this point. It was an estimated 30 degrees Fahrenheit with a windchill of 24, and living up to my fashion standards, I was dressed in a black J. Crew office dress, black Ralph Lauren leather boots and a matching set of pink scarf and gloves. As I walked through the staff gate at the Eisenhower Executive Office Building and placed my purse on the security conveyor belt, one of the Secret Service men jokingly commented to his fellow guards, “Look, boys, she’s Reese Witherspoon from that ‘Legally Blonde’ movie.” I shot a smile and laughed, taking the guard’s comment as a compliment (I am a big fan of Reese) — but I also realized that I might not be taken seriously in my work if I became a victim of my own hair color (the blonde, ditzy sorority-girl type).

One of my responsibilities as a White House Communications intern was to assist the Policy and Procedures office with the compilation of a daily news bulletin, “The Morning Update.” I was in charge of searching for news headlines from major newspapers, highlighting important stories related to President Bush’s policies and important legislation discussed on Capitol Hill. I also conducted research by using LexisNexis to look for quotes from major newspapers’ editorials, senators, state representatives and other individuals for press releases that supported a current policy/issue the President wanted to pass into law. While I was conducting research for “The Morning Update” and press releases in the early days of my internship, I realized I was completely naive about the current events and issues affecting our country. The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (known to all of my co-staffers as “FISA”) was a new term to me. Other than my Tennessee state representatives, I had only heard of Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi and Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid. As for the remaining members of Congress, I was clueless. But my research allowed me to become more familiar with these other important leaders.

My White House internship served as the “ah hah moment” in my life that told me I needed to become more informed of the current political activities transpiring in both Tennessee and Washington. This was also the time when I began reading news publications like “The Washington Post” and “The New York Times”, realizing their articles were more essential than the latest fashion trends modeled on the French couture runway or the latest hairstyles featuring bangs.

So, here I am two years later. I just completed a constituent-services internship for Sen. Bob Corker (R-Tenn.) and am a 2010 college graduate. And I pay attention to the national news, following of the political happenings in D.C. But I miss knowing what’s going on behind the closed doors to the Eisenhower Executive Office Building and sometimes the West Wing.

I owe gratitude to my former co-staffers at the White House Communications Office. Not only did they give me the experience many professionals would envy, but they challenged me in ways I had never been challenged before. By producing press releases, I learned the value of accuracy and efficiency. I became a better team player by working with two male interns from other regions of the country. Ultimately, I began to pay more attention to current events — realizing that it is easier to produce press releases when I actually knew background information about the subject/issue at hand.

While I still remain up-to-date on the latest fashion trends and thumb through the current “Cosmopolitan” while going through the checkout lane at Target, I also fit NBC’s “National News” with Brian Williams in my daily schedule to hear what the latest buzz is on Capitol Hill and around the world. For me, continuing to educate myself on current events is important to not only develop informed positions on certain issues but to also enjoy the foundation of democracy.

Hard truth: Rufus and the Vietnam War Memorial

This essay was written in 1982 for Westward magazine.

By JAY. B. LEWIS

I was standing in the wind before the black marble wall of the Vietnam War Memorial the day before the dedication ceremony. Surrounded by the crowd but completely alone as I found your name – Rufus Hood – the first of so many best friends I’ve had to bury along the trek that brought me here. I was weeping softly, politely, staring at the wall and trying to hold myself together.

The picture that got me was of us sitting out on the fire escape back of the barracks at Fort Polk. High Louisiana summer at Polk. Let’s see, we came in on the 4th of July 1967. You were killed 8 January ’68. That means you only had about six months left on Earth when I knew you. I thought about that, and I remembered how you had this thing about my handwriting, and how you used to dictate all these randy letters to your ladies, and how I’d copy them out longhand and sign your name with a flourish, like on the Declaration of Independence you used to say.

I told all this to a guy from the Big Red One, who had seen me having trouble and come up to help. He coaxed me through it, even closed in to give me cover in case I needed to hide my face. I didn’t.

I mean, that day at the wall there were all kinds of people overcome, each in his own private ritual, with emotions that for years they’d had no time and place to feel. There was a guy from some outfit that had taken heavy abuse, lighting candles before a dozen names on the wall, and a group of Sioux from South Dakota danced by for their dead. And a lot, I don’t know how many but a lot, of people like me, just standing and weeping. And when the guy from the Big Red One saw I was going to be able to do this alone, he took my hand in a thumb-to-thumb Sixties Soul Shake and said, “Welcome home, brother.”

Now, Rufus, ordinarily that scene would be way too honest for Washington, D.C., but there were 100,000 of us in town that week, all hard-looking middle-aged men in cammies and field jackets, a presence that demanded watching just by being there. We could make up our own rules, you see, because there wasn’t anyone around to tell us it was unseemly to cry, unmanly to comfort each other. If we were doing it, then it was proper and right, by definition.

We had all come to mourn men we’d known for a few weeks, months at most, more than a decade ago. Between us we’d buried 57,939 best friends, and now we’d gathered in their names. That may have puzzled outsiders, and that day anyone who hadn’t been to ‘Nam or fed a brother, son, or husband into the war was an outsider. But no one felt the need to explain it: In a generation known for its commitment to causes, we were the only ones who’d staked lives, fortunes, sacred honor on ours. So the attitude was, if you didn’t understand what was happening here in your guts, bones, very soul, then explanations were useless. That felt really good, Rufus, not to have to explain.

I got to tell you about that. See, there was more to the war than just fighting it. I mean, that was just practice. After the war, or after we’d DEROSed, we were scattered like dandelion seeds, and this great freeze settled in on us. We carried our ghosts in silence, for there was no one to tell it to. They – not the enemy, but not exactly friends, either – they still treated us like children, for one thing. Hell, we were children, practically. Teen-agers with old men’s eyes. And, if you talked about it at all, people kept wanting you to explain things that were obvious to anyone with one eye open, or they sat there like stones while you tried to make some sense out of the things that counted. Like naming the dead. And we were alone, with no one there to back us up, to say, “That’s right, listen to the man.”

I got out of the Army and enrolled in college the same day. Straight shot from Fort Polk, where I did my terminal tour, and where I learned you’d been killed. Anyway, I was in school, maybe three weeks after mustering out, this one morning in January when I was walking to the Student Union for breakfast. It was so cold it hurt your lungs. There was this kid out front, shivering in a flannel shirt and no jacket, passing out leaflets denouncing the war. I was going inside where it was warm, so I pulled off my field jacket – which at the time still carried all my colors – and gave it to him to wear while I was inside. I mean, that’s what you’re supposed to do when you see a kid in the cold. Right, Rufus?

Anyway, I came back and he was still there, and we chatted while I got back into my jacket. Then this friend of his came over, pimply kid in a Navy pea coat with a Chairman Mao button. He looks at the patches on my field jacket like he’s just found a clue at the scene of the crime.

“Hey, were you in ‘Nam, man?”

“Yes, in ’68.” Like he’s going to know what that means.

“Did you ever kill anyone, man?” He asks this like a deputy associate district attorney. They all asked that, sometimes as an indictment, sometimes just for titillation.

“Uh, no, I was a combat philatelist. I collected enemy stamps.”

“Now this is what I call a real pig, man,” he says, turning to the kid I’d loaned my jacket to. “I mean this guy doesn’t even care.”

That was bad flashback, Rufus. I still get them, thinking about all the crap I had to take off these kids with their Mao buttons. But what else can you do, you know? Punch out one of the little buggers and you’re just making their point. And besides, you don’t go around hurting people for what they think. It’s not that important. It’s just important enough that when you choke it down, it stays there in a hard knot and never goes away.

There were lots of knots like that untied in Washington during veterans week. We didn’t talk much about the combat, which was different for everyone: some were grunts who’d lived on the edge the whole time, some like me who had just seen institutional craziness. We talked mostly about the homecoming, which was the same for us all. Don’t get me wrong, Rufus, I’m not complaining, certainly not to you. I would have come smiling home to drought, famine and a plague of locusts just to get out of ‘Nam with my hide and my honor intact. My hide was preserved, but if you weren’t careful you lost the honor as soon as you got back to the World. We had to take the rap for losing the war and for all the sins and excesses pursuant thereto. Either that or start turning on each other, blaming our buddies. I still have people telling me to my face, people who are old enough to know better, that the whole thing was a farce and I was an idiot to have gotten into it.

You can take that if you’ve had practice, if you know how to skate the old Zen razor, to control the scene an instant at a time. I mean, I didn’t have that much invested in the war: I only saw my death coming close a couple of times. Mostly for me it was just arrogant brass, babbling staff officers, vile weather, vermin, rodents and a Dear John. I can blow that off … okay, maybe it was all for nothing.

But if I accept that, I also have to accept your death as waste, Rufus. I can’t do that. And even if I could, I’m not going to. And that explains the Wall. This was something we did ourselves. The first thing we all did together. Maybe the first step toward setting things right, toward getting the outsiders straightened out and squared away.

The government, older and wiser as they were, had given us a monument across the Potomac in Arlington Cemetery. A GI standard Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, one each, like the ones for the wars they’d been in. But it’s an empty monument, Rufus, because we have no unknown soldiers. Somehow the older and wiser missed that point. We may be the first American army to lose a war, but we’re one of the few armies since Homer’s time to name all our dead. So we started finding each other a couple of years ago, led by former Spec. 4 Jan Scruggs, and built our own monument, to all our dead individually and severally. And we put it in the most hallowed ground we could find, between the Washington and Lincoln memorials, so no one’s going to forget your name Rufus. Not while Washington, D.C. is standing. By God.

Which brings us to the gathering. That gathering itself was history, Rufus. You could feel it. I don’t know where it fits, but it’s going in there somewhere. People’s history, not politics, a sort of Vietvet’s Woodstock. It frightened people. It even frightened me, at first. Scruggs, who’d come home from a tour as a grunt in the 199th Light Infantry Brigade to do graduate research in psychological trauma among Vietvets, said it even frightened him.

It needn’t have. Oh, it’s true a lot us had trouble handling the freeze, and skated off the razor into self-destructive meltdowns. A lot of the heavy combat victims, guys who’d taken the fry bigtime, had to do it in little pieces, skimming over for the time being and going back later to act the whole ordeal through. Like happens with nightmares: you tamp the terror down for the moment, then bring it back up again when you’re asleep, undistracted, and can face it full on. It’s a hard drill. They say there were as many deaths from suicide as from combat, and I believe it. And a lot of trouble handling jobs, keeping families together, all the problems that arise from having your energy directed inward, which is what you do when you’re carrying a heavy load of rage and you’re public spirited enough to keep it choked down.

Of course, practically nobody noticed us doing that. It was another unacknowledged achievement of our Army, maintaining solitary silence all those years, avoiding the pimply kids who clustered around like flies every time we spoke up. So instead of talking to us, the press mostly reported the same things it had reported on while the war was going. So what you got was this stream of studies that showed conclusively, based on a sampling of 35 or 50 or 116 or however many it was, a sampling of ‘typical’ Vietnam veterans, that all 2.8 million of us were sick and violent and ready to explode into gross violence at any moment. You know, “Vietnam veteran holed up in local apartment. Film at six.” They’re still doing it. And all this time, we’re scattered, and I imagine a fair number of us figured well, I’m harmless, but maybe everyone else who was over there is really a ticking bomb. I mean, it wouldn’t be the weirdest thing to come out of ‘Nam.

Rufus, we blew that stereotype to hell in Washington. The emotion was running high-volt, high-amp from the moment you got on the plane to go. If anyone was going to freak out, it would have been there and then. And no one did. We wept and marched and partied. We talked through pain we’d been carrying our whole adult lives. We abused substances, damn near drank Washington dry, got real loud and real sweet, but we were never dangerous.

I was sitting there in the hallway of the Sheraton Washington, at the reunion of my old outfit, the 9th Division. Down the hall was the Americal. The two outfits had taken over the second floor. There was this guy from the 173rd Airborne – I had his name but someone borrowed my notebook and never found me again – and we were sipping brew and passing smokes, just being brothers, talking this kind-of-Vietnam shorthand, compressed speech that really isn’t speech at all, but a reel-to-reel arching across circuits we’d all found fused into our crania.

He’d been to Dak To. I told him all I knew about Dak To was that coming home, a one-year tour nearly to the day after the battle, that two-thirds of the people on the plane were 173rd, obviously replacements for casualties a year earlier, and that you could read in that that Dak To must have been a real meat-grinder. “Yeah, you got it right,” he says. “That’s all there was.”

That was all we said about the war. We talked mostly about feelings, discovering on every turn of phrase how much we had in common.

“I told my old lady, ‘Honey, I got to go to Washington’,” he says. “And she says, ‘What you want to go up there for and bring all that up again?’ and I says, ‘Honey, you don’t understand. I got to go’.”

“There it is, brother. Same thing at my house. She didn’t understand why, but she could see I had to go.”

This was the second night, Saturday, the day of the parade. We’d marched ten blocks, about 15,000 of us, with people lining the streets six, eight, ten deep, cheering for us, Rufus. I mean, none of us ever in our lives expected to hear that sound. It was sweet; sweeter still was being among the brothers. I’ll probably hurt some feelings by saying this, but since Washington, their esteem is all that counts. They are, after all, the only ones who have proved themselves.

And by that night, outsiders started flashing to this, too, after seeing how fine we were, how we took care of each other. The first night, Friday, the outsiders kind of kept their distance, slipping down the halls, eyes darting around for trouble that just wasn’t there. By Saturday, the party had changed from a wake to a reunion. Sammie Davis, a 9th Division Medal of Honor winner, was there playing his guitar while his wife sang for us. And the outsiders started getting sucked into it: there were children wandering around, listening to our stories while their parents drank our beer; a Japanese businessman came out to listen to Sammie play; there were even a couple of school teachers in their 50s, in town for a convention.

“I’m sure glad we found you boys,” one of them told me. “Your party’s sure a lot more fun than ours. This is the nicest place in Washington to be.”

And it was, by God. Being around people who not only wanted to help but who knew what to do. I mean, here we’d been told, at best, that we were forgiven for being the lowest humanity could sink, and we discover that an inordinately high number of us have showed up in nurturing professions – nursing, teaching, counseling – and all performing on demand, carrying each other through sorrow and anger like we’d carried each other through malaria and trauma wounds.

I’ve been thinking about that a lot, Rufus, trying to pin down what makes us different. I think I’ve about got it figured out. What happened to us in ‘Nam was that we saw the truth. We’d gone over there with a head full of Children’s Crusade ideas, and we’d all gotten them blown away, totally and utterly. Remember John Wayne’s version of the war, the Green Berets? Remember where he walks off into the sunset, holding the Vietnamese kid’s hand, telling him, “You’re what this war’s all about.” Well, what would he have done if the kid had thrown a grenade at him? What would the war have been about then?

I had to ask those kinds of questions, as I sat there in the briefings, listening to the staff planning the evacuation of Khe Sanh around how it would look on television. Talking for hours, while we lost one Rufus Hood a minute. It popped all the illusions like so many soap bubbles: they preached duty, honor, country, and they practiced greed, fear, ignorance. They tried to sell us manhood after the General Patton/Vince Lombardi model, which meant winning, and making someone else lose. And they spent flesh and blood like subway tokens for something as vague as National Honor.

Some guys were blinded by the light, and they came home burnt out and wasted. I saw it with your eyes and that’s what saved me. You probably wouldn’t even remember the day we were coming back from the rifle range. It was the day after we’d pulled off the bandages on our feet and those silver-dollar-sized chunks of hide came off with them. The day they let us ride in the Jeep to give them time to heal.

I still recall the moment, maybe a dozen times a day: dust from the boots, heat from the sun and sand and asphalt, a real convection-oven of a day. The Jeep was trailing the company to police up sunstroke victims, with about five of us stuffed in the back, and little Jimmy Crotts up ahead of us, falling farther and farther behind the column. Remember Crotts, 80 pounds wringing wet, no one could figure out what he was doing in the Army? And that big fat lieutenant – what was his name? – bullying Crotts along, kicking him to his feet every time he fell.

I thought I was going to have to restrain you from running up to that lieutenant and ramming your M-14 into the first orifice you came to. I mean, Rufus, I saw rage, first time I’d ever seen you mad, about 20-years-at-hard-labor’s worth. I tried to explain the basic-training concept, and the chain of command, and all that other airy intellectual crap, and you looked at me like I was crazy and said, “No, listen carefully white boy, there’s nothing happening here but a big old dude bullying a poor little fellow.”

So when I got to ‘Nam and had my childhood burned clean away I had something to fill the vacuum, that fragment of truth you left me like a legacy that day on the road: that you have to watch the people. Nothing else is real. What’s good for people is good, what’s bad for people is bad. And you never, repeat never, let yourself sacrifice people in the worship of concepts. It’s so obvious that reverence for people becomes a definition for sanity.

But if you bring that definition back to the world, you’re really screwed. People here babble about principles and precedents. Like the kid in college: He’d try to make sure your ideology was correct, but it’d never enter his mind to give you his coat. I mean, the twisted, greedy, vicious lunacy runs so far and so deep you find yourself shrinking from it, you want to just dig in, barricade yourself somewhere and hide.

Well, we don’t have to do that anymore. Since Washington, the impulse to cherish and protect that was the high point of ‘Nam is back in vogue. We got a chance to reverse the trend that runs through this whole century, where the warriors have won the wars and the politicians have lost the peace. This time the politicians lost the war, and it’s up to us to win the peace.

That old obsession with macho – the eyeball-to-eyeball ethic that got us into Vietnam and made it such a horror – just has to go. We’re the ones wearing all the medals, and when the country was in a jam, we’re the best they find to pull it out. We don’t have to be men of steel. Steel is strictly 19th Century: we’re some weird new space-age alloy that doesn’t melt in the heat, doesn’t shatter in the cold, doesn’t lose flexibility no matter how many different ways you screw it around. Just the sort you need to get everyone else into the 21st Century.

I think we’re going to pull it off, Rufus, as soon as we get used to the idea of setting the standard. It took ‘Nam and the long freeze to get us in shape for it. That gathering in Washington was the first sign that we’d won. It was a terribly expensive way to rehabilitate the American man, but if it gets us out of the trap we’re in, it may be worth it. So you didn’t die for nothing, Rufus. You saved me, man, Rest easy, now.

A price of war

This essay was written in 2003 for a magazine-writing assignment.

By MELISSA WOZNIAK

I’m on the last cigarette of the night, lost in thought outside my apartment as the neighbors’ lazy conversation drifts down the hallway from their drunken, end-of-semester celebration. They’re playing Bob Dylan. The song Dom loves so much and played obsessively the last time I was in Connecticut, back when our relationship seemed normal, when life seemed normal.

He’d sing along on occasion, and ask me what I thought of this great musical genius who has been a favorite of his for years. I couldn’t understand what the hell Bob Dylan was saying.

And I still can’t, I realize, as I strain to hear the last lingering notes of the familiar song. I wonder if Dom ever thinks of it while he’s in the Middle East, patrolling the hot, desert-encircled city streets. If he ever has moments like this when a single, random memory becomes so vivid he can feel the chill of Connecticut’s late-February air. Or if he blocks the memories because he has to: It’s his job, first and foremost, to stay alive.

I find myself calculating the hours between Dom and myself, an unconscious habit I do throughout the day. He’s starting his shift. I’m headed to bed. And I’m sitting here smoking, trying to clear my head of the day, and the headlines, and the 11 o’clock live broadcast of the flag-draped coffin arriving at McGhee Tyson Airport. I don’t remember the soldier’s name. But he was in the Navy, just like Dom was before he signed up for the highly lucrative – and highly dangerous – work as a government contractor.

CNN can be an unexpectedly powerful addiction. Dom’s plane probably hadn’t even touched down at his war-torn destination before the news channel became a permanent presence in my room. Numbers reeled in a continuous loop on that yellow and black snake of announcements at the bottom of the screen – the number of dead, number of wounded, the number from today and the building number from a year’s involvement in this war. And I would watch, transfixed, with a new sense of attachment to a godforsaken patch of land halfway across the planet.

When someone you love is in the midst of the chaos and fighting, those numbers take on a new meaning: Each one is a face, a life, sometimes of a man who didn’t even see his 20th birthday. And each had someone, a wife – or a girlfriend – who, like me, hasn’t strayed far from CNN and those numbers scrolling across the screen. Whether the rest of America supports the war or opposes it, they can’t comprehend what it’s like to race to the phone on the first ring because they don’t know where their loved one is. Or what an empty, unnerving feeling it is, especially during those first few days, not to know.

DOM SPRANG THE NEWS two days before my birthday.

After attending the funerals of more than one friend killed on a government contract, he had flatly dismissed the lucrative paychecks promised by private security companies as his four-year stretch with the military reached its final months. He was 25; he wanted to buy a house in Fairfield County where he grew up, to have a family one day, to fulfill his longtime dream of going to culinary school. While in the Navy, he watched many of his friends’ personal lives unravel into divorce, one by one, as the strain of long-distance relationships took its toll. It was why he didn’t re-up for another four years with the Navy SEALs, even though he had endured some of the most grueling training of all the military.

In October, Dom picked me up at the airport in Virginia Beach with a glowing smile in his dark eyes and the announcement that he was moving home to finish his degree. It was the happiest I’d seen him in awhile, and we shared the sentiment because I knew how much college meant to him.

But October turned to January, and as spring approached and military funding for his education failed to materialize, the former Navy SEAL who served nine months in Afghanistan found himself at home, on his fourth month of doing nothing. So Dom signed a two-month contract with Blackwater – the first of many he would sign, I was informed. He could see himself doing this for five years, maybe even more. In what seemed like an overnight decision, my other half chose a career that will keep him overseas more than he’ll be at home, doing some of the most high-risk work of the war and doing it without the protection of the U.S. military.

It would pay well – more in one contract than his friends made in a year, he claimed, as if that would change my resentment toward the job. Suddenly the concept of money seemed to take command over all form of reason, to become somewhat of an addiction in itself. It crept into every conversation. It instigated fights over subjects that didn’t even relate to the contracts. It became the guiding priority in his life, the way to buy that house in Fairfield County and retire before he was 30.

If he came back alive, I’d remind him.

Dom couldn’t even tell me what country he was going to. “Classified information,” he would insist, growing defensive at the onset of another heated argument:

Iraq’s a big country. So are Pakistan and Afghanistan. He’s telling me he can’t at least let me know which country he’s going to so I can narrow down, however slightly, what to worry about on the news each night? It was because I loved him, not because I wanted to threaten national security, that I pushed the subject, but I don’t think Dom understood that.

He was not going to Iraq. That’s about all I could get from him.

TWO WEEKS LATER, the gruesome pictures of that burning American truck in Fallujah filled the screen on CNN all evening. They weren’t airing the most graphic footage, broadcasters reported. But images of billowing flames that swallowed the truck and consumed the four contractors inside recounted their death at the hands of a gleeful mob of Iraqis in brutal detail.

The contractors were with Blackwater. They were part of Dom’s company, doing the same job, and now their remains were hanging from a bridge, murdered by the people they were sent to help.

For hours, I sat motionless in front of the TV, a sinking knot of reality settling in my stomach as I watched the same footage repeat in succession. I knew it wasn’t Dom. I knew he wasn’t in Iraq. But I kept picturing his face, his hands – these were men in his company. It just as easily could have been him.

I mourned the little boy somewhere who was watching his daddy hang from that bridge without knowing it was him. I felt the swelling anger toward that surreal, exuberant mob that seemed beyond human, and decided that the whole country could be bombed off the planet for all I cared at the moment.

Mostly I wondered what was running through the minds of those four contractors as the fiery walls of their truck closed in. It’s safe to assume that they weren’t thinking of the money they made with the job.

CNN became more than a 24-hour war bulletin to me. It became a story of the people behind the conflict, the lives that were changed by the decisions of a single man in the White House. Would George W. Bush still have that confident smirk that’s become a trademark of his speeches on conquering the “enemies of freedom” if his daughter Barbara served in the National Guard with the Witmer sisters? Did he think of his own family – his own daughters – as the two surviving girls bade a tearful goodbye to 20-year-old Michelle during the national broadcast of her funeral?

The President can send his condolences to the wife of the captured civilian contractor who was imprisoned for A MONTH as a tool of negotiation, but his own family is home safe in the White House. The assurance that Thomas Hamill was defending freedom hardly could have brought comfort to a family who didn’t know where he was, or if he was even still alive after the deadline set by his captors passed three weeks.

The man’s eyes held a frightened vulnerability on the television footage from Iraq that still lingers in my mind. Here’s a father of two, a dairy farmer from Mississippi, just trying to earn money to feed his family.

I wonder how Dom reacts to the news of Tom Hamill, or of his fallen Blackwater colleagues, or of the scores of other contractors who were lured by the money but lost in the end. Do these people cross his mind during the long, solitary hours on night watch? I’m not sure if he even thinks of me. He’s said it before: Over there you either maintain your focus or risk getting killed. So I keep these questions to myself, along with all the other churning emotions that I’m dealing with, alone, on the other side of the world.

IT’S ALMOST A YEAR AGO to the day since Dom returned from his nine-month deployment in Afghanistan and we first met. He was in perfect shape, confident, full of stories and pictures from the war. But the more time we spent together, the more I realized that the military was a part of him he would never completely reveal. He hated the adulating hero treatment he’d get whenever someone would find out he had served abroad. He grew uncomfortable whenever politics became a topic for bar discussion, or if people wanted to know how many terrorists he’d killed or how much action he saw.

“It’s my job,” he told me once. “People shouldn’t make such a big deal out of it.”

Dom went through some of the toughest training in the world to get where he was, 25 weeks of brutal endurance tests that only a handful in the class would see to the end. He shared pieces of his BUD/s training with me: About reaching the brink of hypothermia, the hallucinations that came with only four hours of sleep during Hell Week, the nights he and his buddies would down a bottle of Jim Beam despite the day’s physical exhaustion. BUD/s and Afghanistan were things I knew about him — but only to a point.

He was trained not to feel, and I know the wall is up during his shift even as I write. The lack of emotion carries over to the daily e-mails and sporadic phone calls that keep us connected, however tenuously, to each other’s life. Last night it was 11 minutes and 29 seconds, hardly enough time to get used to hearing Dom’s voice, much less analyze the feelings behind it: Whether he’s scared and lonely or truly happy, or if he’s just telling me that to keep me from worrying. “It’s not that bad over here,” he says. “Really, it’s great. Feels like home.”

I ramble on about my day as if we’re separated by several hundred miles instead of the Atlantic Ocean and several time zones. I want to ask him where he is, what he’s doing, what he had for dinner last night. I want to tell him the dirty joke I heard at work without it feeling as inappropriate as cursing in church. Instead, we continue a relatively bullshit conversation about the weather and his pending return date, acutely aware of the government presence monitoring the call from some cubicle deep inside the Pentagon.

“Don’t ask about anything that goes on over here,” he warned before he left. So I don’t. And I try not to cry, or to raise my voice at him for leaving me with a relationship that has become a grand understatement of “long-distance,” one he expects me to keep up single-handedly.

He’s been gone for a month and has another to go. CNN is still my addiction. But I’m becoming more preoccupied with how life will be when he returns because I’ve learned to trust when he says he’ll be OK over there. How can someone go from the security of America to guarding his life with a gun on the unstable outskirts of a foreign city, then back to America in the course of three months? I visualize what he’s doing when he’s alone more than I do about his hours on patrol. I wish I could be some sort of comfort, to hold him and tell him everything’s all right.

But it’s not, because nothing’s fair about the situation he left at home. I wasn’t a factor in his decision to make these contracts a career. Dom wasn’t sent to fight as a Navy SEAL; he went on his own free will, as a civilian contractor. He knows that the months apart are going to be hard, that it will get worse before it gets better. But he refuses to face what it’s like on my side of the world, to be completely in love, obsessively anxious, yet increasingly angry that he expects me to maintain a relationship based entirely on those once-a-week phone calls when he’s the one who created the predicament.

AT NIGHT DOM WOULD often twitch as he drifted out of the reach of consciousness. I’d lie awake watching his trembling eyelids, wondering what he sees when he sleeps. Are there nights when he’s transported back to Afghanistan to relive the things he can’t talk about? There’s a side of him I’ll never know; these two months will pass by unspoken between us, to join that part of his life.

I’m scared that he has changed over there, that the instinct to close off emotion will be brought home along with his luggage and guns when he steps off the plane May 22. I want to see the same tall, easygoing Italian with his lovably sarcastic sense of humor and see him smile at me the same way he did a year ago. I want to resume the conversations we had in Little Italy over pasta and wine about hopes and dreams, to dance to Frank Sinatra without saying a word, completely at ease with each other. Maybe Dom will one day realize that his talents offer a future beyond a series of government contracts. I cling to this hope, refusing to acknowledge that separation may become a way of life.

More than anything, I hate these empty conversations over miles of ocean and the feeling that we’ve lost each other after only a month. I hate the war. And I hate that thousands of other women are going through the same thing, watching CNN and silently hoping it was someone else who was killed today. Dom is oblivious of the warring emotions he left me with that sometimes seem more intense than the fighting in Fallujah – and that’s what I’ve grown to hate most over the past six weeks.

I’m 21. I should be worried about finals, not the June 30 turnover of Iraq, and whether that will ignite a new wave of violence, since Dom is set to return to the Middle East in July. In the remaining days of this first contract, all I can do is wait and pray that he’s safe. And quietly wish that something will change his mind and keep him home.

Can you say … “Hero”? — Fred Rogers has been doing the same small good thing for a very long time

Tom Junod’s profile of Mr. Rogers was the cover story of the November 1998 issue of Esquire magazine. Junod is a writer-at-large at Esquire.

By TOM JUNOD

ONCE UPON A TIME, a little boy loved a stuffed animal whose name was Old Rabbit. It was so old, in fact, that it was really an unstuffed animal; so old that even back then, with the little boy’s brain still nice and fresh, he had no memory of it as “Young Rabbit,” or even “Rabbit”; so old that Old Rabbit was barely a rabbit at all but rather a greasy hunk of skin without eyes and ears, with a single red stitch where its tongue used to be. The little boy didn’t know why he loved Old Rabbit; he just did, and the night he threw it out the car window was the night he learned how to pray. He would grow up to become a great prayer, this little boy, but only intermittently, only fitfully, praying only when fear and desperation drove him to it, and the night he threw Old Rabbit into the darkness was the night that set the pattern, the night that taught him how. He prayed for Old Rabbit’s safe return, and when, hours later, his mother and father came home with the filthy, precious strip of rabbity roadkill, he learned not only that prayers are sometimes answered but also the kind of severe effort they entail, the kind of endless frantic summoning. And so when he threw Old Rabbit out the car window the next time, it was gone for good.

YOU WERE A CHILD ONCE, TOO. That’s what Mister Rogers said, that’s what he wrote down, once upon a time, for the doctors. The doctors were ophthalmologists. An ophthalmologist is a doctor who takes care of the eyes. Sometimes, ophthalmologists have to take care of the eyes of children, and some children get very scared, because children know that their world disappears when their eyes close, and they can be afraid that the ophthalmologists will make their eyes close forever. The ophthalmologists did not want to scare children, so they asked Mister Rogers for help, and Mister Rogers agreed to write a chapter for a book the ophthalmologists were putting together — a chapter about what other ophthalmologists could do to calm the children who came to their offices. Because Mister Rogers is such a busy man, however, he could not write the chapter himself, and he asked a woman who worked for him to write it instead. She worked very hard at writing the chapter, until one day she showed what she had written to Mister Rogers, who read it and crossed it all out and wrote a sentence addressed directly to the doctors who would be reading it: “You were a child once, too.”

And that’s how the chapter began.

THE OLD NAVY-BLUE SPORT JACKET comes off first, then the dress shoes, except that now there is not the famous sweater or the famous sneakers to replace them, and so after the shoes he’s on to the dark socks, peeling them off and showing the blanched skin of his narrow feet. The tie is next, the scanty black batwing of a bow tie hand-tied at his slender throat, and then the shirt, always white or light blue, whisked from his body button by button. He wears an undershirt, of course, but no matter — soon that’s gone, too, as is the belt, as are the beige trousers, until his undershorts stand as the last impediment to his nakedness. They are boxers, egg-colored, and to rid himself of them he bends at the waist, and stands on one leg, and hops, and lifts one knee toward his chest and then the other and then … Mister Rogers has no clothes on.

Nearly every morning of his life, Mister Rogers has gone swimming, and now, here he is, standing in a locker room, seventy years old and as white as the Easter Bunny, rimed with frost wherever he has hair, gnawed pink in the spots where his dry skin has gone to flaking, slightly wattled at the neck, slightly stooped at the shoulder, slightly sunken in the chest, slightly curvy at the hips, slightly pigeoned at the toes, slightly aswing at the fine bobbing nest of himself… and yet when he speaks, it is in that voice, his voice, the famous one, the unmistakable one, the televised one, the voice dressed in sweater and sneakers, the soft one, the reassuring one, the curious and expository one, the sly voice that sounds adult to the ears of children and childish to the ears of adults, and what he says, in the midst of all his bobbing nudity, is as understated as it is obvious: “Well, Tom, I guess you’ve already gotten a deeper glimpse into my daily routine than most people have.”

ONCE UPON A TIME, a tong time ago, a man took off his jacket and put on a sweater. Then he took off his shoes and put on a pair of sneakers. His name was Fred Rogers. He was starting a television program, aimed at children, called Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. He had been on television before, but only as the voices and movements of puppets, on a program called The Children’s Corner. Now he was stepping in front of the camera as Mister Rogers, and he wanted to do things right, and whatever he did right, he wanted to repeat. And so, once upon a time, Fred Rogers took off his jacket and put on a sweater his mother had made him, a cardigan with a zipper. Then he took off his shoes and put on a pair of navy-blue canvas boating sneakers. He did the same thing the next day, and then the next … until he had done the same things, those things, 865 times, at the beginning of 865 television programs, over a span of thirty-one years. The first time I met Mister Rogers, he told me a story of how deeply his simple gestures had been felt, and received. He had just come back from visiting Koko, the gorilla who has learned — or who has been taught — American Sign Language. Koko watches television. Koko watches Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, and when Mister Rogers, in his sweater and sneakers, entered the place where she lives, Koko immediately folded him in her long, black arms, as though he were a child, and then … “She took my shoes off, Tom,” Mister Rogers said.

Koko was much bigger than Mister Rogers. She weighed 280 pounds, and Mister Rogers weighed 143. Koko weighed 280 pounds because she is a gorilla, and Mister Rogers weighed 143 pounds because he has weighed 143 pounds as long as he has been Mister Rogers, because once upon a time, around thirty-one years ago, Mister Rogers stepped on a scale, and the scale told him that Mister Rogers weighs 143 pounds. No, not that he weighed 143 pounds, but that he weighs 143 pounds…. And so, every day, Mister Rogers refuses to do anything that would make his weight change — he neither drinks, nor smokes, nor eats flesh of any kind, nor goes to bed late at night, nor sleeps late in the morning, nor even watches television — and every morning, when he swims, he steps on a scale in his bathing suit and his bathing cap and his goggles, and the scale tells him he weighs 143 pounds. This has happened so many times that Mister Rogers has come to see that number as a gift, as a destiny fulfilled, because, as he says, “the number 143 means ‘I love you.’ It takes one letter to say ‘I’ and four letters to say ‘love’ and three letters to say ‘you.’ One hundred and forty-three. ‘I love you.’ Isn’t that wonderful?”

THE FIRST TIME I CALLED MISTER ROGERS on the telephone, I woke him up from his nap. He takes a nap every day in the late afternoon — just as he wakes up every morning at five-thirty to read and study and write and pray for the legions who have requested his prayers; just as he goes to bed at nine-thirty at night and sleeps eight hours without interruption. On this afternoon, the end of a hot, yellow day in New York City, he was very tired, and when I asked if I could go to his apartment and see him, he paused for a moment and said shyly, “Well, Tom, I’m in my bathrobe, if you don’t mind.” I told him I didn’t mind, and when, five minutes later, I took the elevator to his floor, well, sure enough, there was Mister Rogers, silver-haired, standing in the golden door at the end of the hallway and wearing eyeglasses and suede moccasins with rawhide laces and a flimsy old blue-and-yellow bathrobe that revealed whatever part of his skinny white calves his dark-blue dress socks didn’t hide. “Welcome, Tom,” he said with a slight bow, and bade me follow him inside, where he lay down — no, stretched out, as though he had known me all his life — on a couch upholstered with gold velveteen. He rested his head on a small pillow and kept his eyes closed while he explained that he had bought the apartment thirty years before for $11,000 and kept it for whenever he came to New York on business for the Neighborhood. I sat in an old armchair and looked around. The place was drab and dim, with the smell of stalled air and a stain of daguerreotype sunlight on its closed, slatted blinds, and Mister Rogers looked so at home in its gloomy familiarity that I thought he was going to fall back asleep when suddenly the phone rang, startling him. “Oh, hello, my dear,” he said when he picked it up, and then he said that he had a visitor, someone who wanted to learn more about the Neighborhood. “Would you like to speak to him?” he asked, and then handed me the phone: “It’s Joanne,” he said. I took the phone and spoke to a woman — his wife, the mother of his two sons — whose voice was hearty and almost whooping in its forthrightness and who spoke to me as though she had known me for a long time and was making the effort to keep up the acquaintance. When I handed him back the phone, he said, “Bye, my dear,” and hung up and curled on the couch like a cat, with his bare calves swirled underneath him and one of his hands gripping his ankle, so that he looked as languorous as an odalisque. There was an energy to him, however, a fearlessness, an unashamed insistence on intimacy; and though I tried to ask him questions about himself, he always turned the questions back on me, and when I finally got him to talk about the puppets that were the comfort of his lonely boyhood, he looked at me, his gray-blue eyes at once mild and steady; and asked, “What about you, Tom? Did you have any special friends growing up?”

“Special friends?”

“Yes,” he said. “Maybe a puppet, or a special toy, or maybe just a stuffed animal you loved very much. Did you have a special friend like that, Tom?”

“Yes, Mister Rogers.”

“Did your special friend have a name, Tom?”

“Yes, Mister Rogers. His name was Old Rabbit.”

“Old Rabbit. Oh, and I’ll bet the two of you were together since he was a very young rabbit. Would you like to tell me about Old Rabbit, Tom?”

And it was just about then, when I was spilling the beans about my special friend, that Mister Rogers rose from his corner of the couch and stood suddenly in front of me with a small black camera in hand. “Can I take your picture, Tom?” he asked. “I’d like to take your picture. I like to take pictures of all my new friends, so that I can show them to Joanne…. “And then, in the dark room, there was a wallop of white light, and Mister Rogers disappeared behind it.

ONCE UPON A TIME, there was a boy who didn’t like himself very much. It was not his fault. He was born with cerebral palsy. Cerebral palsy is something that happens to the brain. It means that you can think but sometimes can’t walk, or even talk. This boy had a very bad case of cerebral palsy, and when he was still a little boy; some of the people entrusted to take care of him took advantage of him instead and did things to him that made him think that he was a very bad little boy, because only a bad little boy would have to live with the things he had to live with. In fact, when the little boy grew up to be a teenager, he would get so mad at himself that he would hit himself, hard, with his own fists and tell his mother, on the computer he used for a mouth, that he didn’t want to live anymore, for he was sure that God didn’t like what was inside him any more than he did. He had always loved Mister Rogers, though, and now, even when he was fourteen years old, he watched the Neighborhood whenever it was on, and the boy’s mother sometimes thought that Mister Rogers was keeping her son alive. She and the boy lived together in a city in California, and although she wanted very much for her son to meet Mister Rogers, she knew that he was far too disabled to travel all the way to Pittsburgh, so she figured he would never meet his hero, until one day she learned through a special foundation designed to help children like her son that Mister Rogers was coming to California and that after he visited the gorilla named Koko, he was coming to meet her son.

At first, the boy was made very nervous by the thought that Mister Rogers was visiting him. He was so nervous, in fact, that when Mister Rogers did visit, he got mad at himself and began hating himself and hitting himself, and his mother had to take him to another room and talk to him. Mister Rogers didn’t leave, though. He wanted something from the boy, and Mister Rogers never leaves when he wants something from somebody. He just waited patiently; and when the boy came back, Mister Rogers talked to him, and then he made his request. He said, “I would like you to do something for me. Would you do something for me?” On his computer, the boy answered yes, of course, he would do anything for Mister Rogers, so then Mister Rogers said, “I would like you to pray for me, Will you pray for me?” And now the boy didn’t know how to respond. He was thunderstruck. Thunderstruck means that you can’t talk, because something has happened that’s as sudden and as miraculous and maybe as scary as a bolt of lightning, and all you can do is listen to the rumble. The boy was thunderstruck because nobody had ever asked him for something like that, ever. The boy had always been prayed for. The boy had always been the object of prayer, and now he was being asked to pray for Mister Rogers, and although at first he didn’t know if he could do it, he said he would, he said he’d try, and ever since then he keeps Mister Rogers in his prayers and doesn’t talk about wanting to die anymore, because he figures Mister Rogers is close to God, and if Mister Rogers likes him, that must mean God likes him, too.

As for Mister Rogers himself … well, he doesn’t look at the story in the same way that the boy did or that I did. In fact, when Mister Rogers first told me the story, I complimented him on being so smart — for knowing that asking the boy for his prayers would make the boy feel better about himself — and Mister Rogers responded by looking at me at first with puzzlement and then with surprise. “Oh, heavens no, Tom! I didn’t ask him for his prayers for him; I asked for me. I asked him because I think that anyone who has gone through challenges like that must be very close to God. I asked him because I wanted his intercession.”

ON DECEMBER 1, 1997 — oh, heck, once upon a time — a boy, no longer little, told his friends to watch out, that he was going to do something “really big” the next day at school, and the next day at school he took his gun and his ammo and his earplugs and shot eight classmates who had clustered for a prayer meeting. Three died, and they were still children, almost. The shootings took place in West Paducah, Kentucky, and when Mister Rogers heard about them, he said, “Oh, wouldn’t the world be a different place if he had said, ‘I’m going to do something really little tomorrow,'” and he decided to dedicate a week of the Neighborhood to the theme “Little and Big.” He wanted to tell children that what starts out little can sometimes become big, and so they could devote themselves to little dreams without feeling bad about them. But how could Mister Rogers show little becoming big, and vice versa? That was a challenge. He couldn’t just say it, the way he could always just say to the children who watch his program that they are special to him, or even sing it, the way he could always just sing “It’s You I Like” and “Everybody’s Fancy” and “It’s Such a Good Feeling” and “Many Ways to Say I Love You” and “Sometimes People Are Good.” No, he had to show it, he had to demonstrate it, and that’s how Mister Rogers and the people who work for him eventually got the idea of coming to New York City to visit a woman named Maya Lin.

Maya Lin is a famous architect. Architects are people who create big things from the little designs they draw on pieces of paper. Most famous architects are famous for creating big famous buildings, but Maya Lin is more famous for creating big fancy things for people to look at, and in fact, when Mister Rogers had gone to her studio the day before, he looked at the pictures she had drawn of the clock that is now on the ceiling of a place in New York called Penn Station. A clock is a machine that tells people what time it is, but as Mister Rogers sat in the backseat of an old station wagon hired to take him from his apartment to Penn Station, he worried that Maya Lin’s clock might be too fancy and that the children who watch the Neighborhood might not understand it. Mister Rogers always worries about things like that, because he always worries about children, and when his station wagon stopped in traffic next to a bus stop, he read aloud the advertisement of an airline trying to push its international service. “Hmmm,” Mister Rogers said, “that’s a strange ad. `Most people think of us as a great domestic airline. We hate that.’ Hmmm. Hate is such a strong word to use so lightly. If they can hate something like that, you wonder how easy it would be for them to hate something more important.” He was with his producer, Margy Whitmer. He had makeup on his face and a dollop of black dye combed into his silver hair. He was wearing beige pants, a blue dress shirt, a tie, dark socks, a pair of dark-blue boating sneakers, and a purple, zippered cardigan. He looked very little in the backseat of the car. Then the car stopped on Thirty-fourth Street, in front of the escalators leading down to the station, and when the doors opened–

“Holy shit! It’s Mister Fucking Rogers!”

— he turned into Mister Fucking Rogers. This was not a bad thing, however, because he was in New York, and in New York it’s not an insult to be called Mister Fucking Anything. In fact, it’s an honorific. An honorific is what people call you when they respect you, and the moment Mister Rogers got out of the car, people wouldn’t stay the fuck away from him, they respected him so much. Oh, Margy Whitmer tried to keep people away from him, tried to tell people that if they gave her their names and addresses, Mister Rogers would send them an autographed picture, but every time she turned around, there was Mister Rogers putting his arms around someone, or wiping the tears off someone’s cheek, or passing around the picture of someone’s child, or getting on his knees to talk to a child. Margy couldn’t stop them, and she couldn’t stop him. “Oh, Mister Rogers, thank you for my childhood,” “Oh, Mister Rogers, you’re the father I never had.” “Oh, Mister Rogers, would you please just hug me?” After a while, Margy just rolled her eyes and gave up, because it’s always like this with Mister Rogers, because the thing that people don’t understand about him is that he’s greedy for this — greedy for the grace that people offer him. What is grace? He doesn’t even know. He can’t define it. This is a man who loves the simplifying force of definitions, and yet all he knows of grace is how he gets it; all he knows is that he gets it from God, through man. And so in Penn Station, where he was surrounded by men and women and children, he had this power, like a comic-book superhero who absorbs the energy of others until he bursts out of his shirt.

“If Mister Fucking Rogers can tell me how to read that fucking clock, I’ll watch his show every day for a fucking year” — that’s what someone in the crowd said while watching Mister Rogers and Maya Lin crane their necks at Maya Lin’s big fancy clock, but it didn’t even matter whether Mister Rogers could read the clock or not, because every time he looked at it, with the television cameras on him, he leaned back from his waist and opened his mouth wide with astonishment, like someone trying to catch a peanut he had tossed into the air, until it became clear that Mister Rogers could show that he was astonished all day if he had to, or even forever, because Mister Rogers lives in a state of astonishment, and the astonishment he showed when he looked at the clock was the same astonishment he showed when people — absolute strangers — walked up to him and fed his hungry ear with their whispers, and he turned to me, with an open, abashed mouth, and said, “Oh, Tom, if you could only hear the stories I hear!”

ONCE UPON A TIME, Mister Rogers went to New York City and got caught in the rain. He didn’t have an umbrella, and he couldn’t find a taxi, either, so he ducked with a friend into the subway and got on one of the trains. It was late in the day, and the train was crowded with children who were going home from school. Though of all races, the schoolchildren were mostly black and Latino, and they didn’t even approach Mister Rogers and ask him for his autograph. They just sang. They sang, all at once, all together, the song he sings at the start of his program, “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?” and turned the clattering train into a single soft, runaway choir.

HE FINDS ME, OF COURSE, AT PENN STATION. He finds me, because that’s what Mister Rogers does — he looks, and then he finds. I’m standing against a wall, listening to a bunch of mooks from Long Island discuss the strange word — χáρις — he has written down on each of the autographs he gave them. First mook: “He says it’s the Greek word for grace.” Second mook: “Huh. That’s cool. I’m glad I know that. Now, what the fuck is grace?” First mook: “Looks like you’re gonna have to break down and buy a dictionary.” Second mook: “fuck that. What I’m buying is a ticket to the fucking Lotto. I just met Mister Rogers — this is definitely my lucky day.” I’m listening to these guys when, from thirty feet away, I notice Mister Rogers looking around for someone and know, immediately; that he is looking for me. He is on one knee in front of a little girl who is hoarding, in her arms, a small stuffed animal, sky-blue, a bunny.

“Remind you of anyone, Tom?” he says when I approach the two of them. He is not speaking of the little girl.

“Yes, Mister Rogers.”

“Looks a little bit like … Old Rabbit, doesn’t it, Tom?”

“Yes, Mister Rogers.”

“I thought so.” Then he turns back to the little girl. “This man’s name is Tom. When he was your age, he had a rabbit, too, and he loved it very much. Its name was Old Rabbit. What is yours named?”

The little girl eyes me suspiciously, and then Mister Rogers. She goes a little knock-kneed, directs a thumb toward her mouth. “Bunny Wunny,” she says.

“Oh, that’s a nice name,” Mister Rogers says, and then goes to the Thirty-fourth Street escalator to climb it one last time for the cameras. When he reaches the street, he looks right at the lens, as he always does, and says, speaking of the Neighborhood, “Let’s go back to my place,” and then makes a right turn toward Seventh Avenue, except that this time he just keeps going, and suddenly Margy Whitmer is saying, “Where is Fred? Where is Fred?” and Fred, he’s a hundred yards away, in his sneakers and his purple sweater, and the only thing anyone sees of him is his gray head bobbing up and down amid all the other heads, the hundreds of them, the thousands, the millions, disappearing into the city and its swelter.

ONCE UPON A TIME, a little boy with a big sword went into battle against Mister Rogers. Or maybe, if the truth be told, Mister Rogers went into battle against a little boy with a big sword, for Mister Rogers didn’t like the big sword. It was one of those swords that really isn’t a sword at all; it was a big plastic contraption with lights and sound effects, and it was the kind of sword used in defense of the universe by the heroes of the television shows that the little boy liked to watch. The little boy with the big sword did not watch Mister Rogers. In fact, the little boy with the big sword didn’t know who Mister Rogers was, and so when Mister Rogers knelt down in front of him, the little boy with the big sword looked past him and through him, and when Mister Rogers said, “Oh, my; that’s a big sword you have,” the boy didn’t answer, and finally his mother got embarrassed and said, “Oh, honey, c’mon, that’s Mister Rogers,” and felt his head for fever. Of course, she knew who Mister Rogers was, because she had grown up with him, and she knew that he was good for her son, and so now, with her little boy zombie-eyed under his blond bangs, she apologized, saying to Mister Rogers that she knew he was in a rush and that she knew he was here in Penn Station taping his program and that her son usually wasn’t like this, he was probably just tired … Except that Mister Rogers wasn’t going anywhere. Yes, sure, he was taping, and right there, in Penn Station in New York City, were throngs of other children wiggling in wait for him, but right now his patient gray eyes were fixed on the little boy with the big sword, and so he stayed there, on one knee, until the little boy’s eyes finally focused on Mister Rogers, and he said, “It’s not a sword; it’s a death ray.” A death ray! Oh, honey, Mommy knew you could do it … And so now, encouraged, Mommy said, “Do you want to give Mister Rogers a hug, honey?” But the boy was shaking his head no, and Mister Rogers was sneaking his face past the big sword and the armor of the little boy’s eyes and whispering something in his ear — something that, while not changing his mind about the hug, made the little boy look at Mister Rogers in a new way, with the eyes of a child at last, and nod his head yes.

We were heading back to his apartment in a taxi when I asked him what he had said.

“Oh, I just knew that whenever you see a little boy carrying something like that, it means that he wants to show people that he’s strong on the outside.

“I just wanted to let him know that he was strong on the inside, too.

“And so that’s what I told him.

“I said, `Do you know that you’re strong on the inside, too?’

“Maybe it was something he needed to hear.”

HE WAS BARELY MORE THAN A BOY himself when he learned what he would be fighting for, and fighting against, for the rest of his life. He was in college. He was a music major at a small school in Florida and planning to go to seminary upon graduation. His name was Fred Rogers. He came home to Latrobe, Pennsylvania, once upon a time, and his parents, because they were wealthy, had bought something new for the corner room of their big redbrick house. It was a television. Fred turned it on, and, as he says now, with plaintive distaste, “there were people throwing pies at one another.” He was the soft son of overprotective parents, but he believed, right then, that he was strong enough to enter into battle with that — that machine, that medium — and to wrestle with it until it yielded to him, until the ground touched by its blue shadow became hallowed and this thing called television came to be used “for the broadcasting of grace through the land.” It would not be easy, no — for in order to win such a battle, he would have to forbid himself the privilege of stopping, and whatever he did right he would have to repeat, as though he were already living in eternity. And so it was that the puppets he employed on The Children’s Comer would be the puppets he employed forty-four years later, and so it was that once he took off his jacket and his shoes … well, he was Mister Rogers for good. And even now, when he is producing only three weeks’ worth of new programs a year, he still winds up agonizing — agonizing — about whether to announce his theme as “Little and Big” or “Big and Little” and still makes only two edits per televised minute, because he doesn’t want his message to be determined by the cuts and splices in a piece of tape — to become, despite all his fierce coherence, “a message of fragmentation.”